the tangled path, after turning left and right countless times—or, at least, so it seemed to him—dawned like a pale glow. He first heard the breath of the Beast; then he saw it, lying on its side. It slept, heavy in sleep and as if innocent...Suddenly, hearing the faint noise of the mortal...the Beast...was instantly awake...The two looked at each other. There was little space between the two. The hero threw himself on the animal and...plunged his sword into its body. [LLL 32]

Directionality

What other characteristic does the lived space have? Its directionality. The human space always has a direction: forward and backward, an up and down, a left and a right. One is always oriented in space and on the way to somewhere. On our bed we sleep leaning to the left or to the right; we get up on one of the two sides, we go out to the street and head toward work, which is north, south, east, or west from where we are. In the late afternoon, we leave work and return home in the opposite direction. Straus argues that there is only one situation in which human beings lose their frontality and that is dance (FR 164-76). When dancing, the human being indistinctly moves forwards or backwards, toward the left or toward the right and does not advance. Here the space is not frontal, but circular. And perhaps for that same reason dancing has such a relaxing and reposing effect, for, when dancing, one of the deepest characteristics of human life, which is its directionality, and consequently, its intentionality, is suspended. And when this occurs, life ceases, at least for a moment, to be a challenge, an invitation to action, to the performance of work.

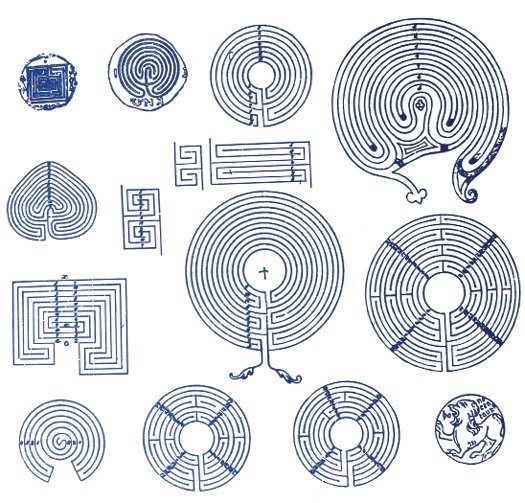

The labyrinthine space, in contrast, lacks all direction: forward is confused with backward and one side is mistaken for the other, there is an entrance but no exit and the center is an illusion. The reason for this total disorientation is the structure of this space

itself, constantly ending in a wall, open on two equal and mirrored sides, leading to new Y-junctions in the passages that are also identical, and ultimately, to the same point of departure. But the creepiness of the atmosphere also contributes to this disorientation. Its association with the underground, with grottos, with darkness and the lack of any form of luminosity is another essential feature of the labyrinth. The word "orientation" comes from "orient" or east, that is, the place where one can see the sun rising in the morning and that solar journey from the east to the west is what has served as a starting point regarding orientation for most of the peoples on earth. The lack of reference to the movement of the sun that is inherent to the labyrinth necessarily contributes, therefore, to the total disorientation of everyone who enters that space.

Referentiality

Another characteristic of the human or lived space is its permanently being referred to a space other than itself. In that respect, it is similar to all psychic phenomena, which, as we know from Franz Brentano9 and Edmund Husserl,10 are essentially characterized by being referred to things other than themselves, that is to say, by their intentionality. Every interior space, with its multiple meanings, refers to an exterior space; yet this occurs also in reference to elemental spaces, such as the dimension of height, in which down remits to up, the dimension of width, in which the left side remits to the right side and finally, the dimension

9 Franz Brentano, Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkt. Zweiter Band: Von der Klassifikation der Psychischen Phänomene, Leipzig, DE: Felix Meiner Verlag 1925, pp. 133-50.

10 Edmund Husserl, Phänomenologische Psychologie, ed. Walter Biemel, Den Haag, NL: Martinus Nijhoff, 1962.

Figure 4: Different forms of labyrinthine design (LLL 48).