of depth in which forward remits to backward. But this sort of intentionality of the human space also appears in more elaborated forms of spatiality, as is the case of the home, which, as the center of the world, remits to the street, to the road and its possible ends, but also to the square,11 to the agora, as a resting place on the road and a place of encounter with the other. Yet one of the forms of space where a reference to another space is observed most clearly is the case of the profane space versus the sacred space. Since the appearance of human beings on the phylogenic scale, that duality arises in them and just as there is a profane time, the one of temporality and a time of the gods, the time of the eternal, to which one is admitted through ritual act, in the same way the space of the home and of the wide world remit to the sacred space, to a transcendent space, or plainly stated, to another world. In the Christian tradition the lord's prayer has been prayed for two thousand years and this prayer contains already in the first phrase the

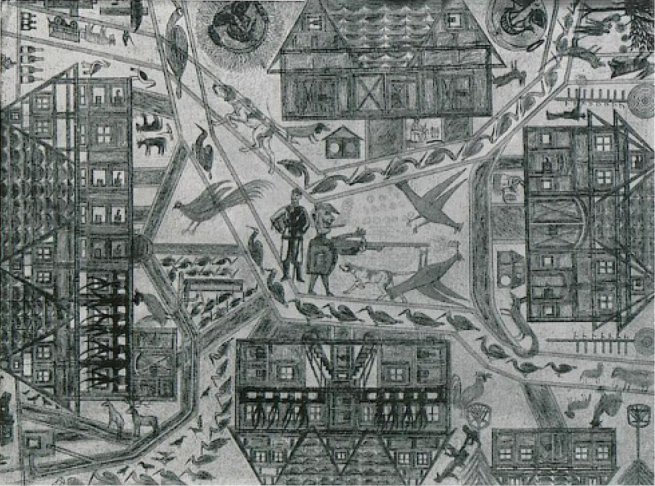

11 Hans Prinzhorn, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken: Ein Beitrag zur Psychologie und Psychopathologie der Gestaltung, Berlin, DE: Verlag Julius Springer 1922, p. 225, Case 90, Fig. 126, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/prinzhorn1922/0001/info,text_ocr,thumbs. [Henceforth cited as BG] © Sammlung Prinzhorn, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg.

presence of the sacred space: "Our Father, who art in Heaven."

One of the spatial polarities most relevant to the theme of the labyrinth that is of interest today is the one given between the nocturnal space and the daytime space, between darkness and light; a polarity that is discussed in great detail by Tellenbach.12 It is true that the Greek world did not have such a negative view of shadows as the Judeo-Christian tradition does. For the Greeks the night was the time of seeing their gods and heroes in the firmament. Moreover, the road from the daytime toward the night of death was not irreversible for them, as can be inferred from the myth of Persephone, kidnapped by Hades, the sovereign of hell, who, grown tired of his celibacy, forced her to be his wife. Zeus took pity on her and allowed Hermes to bring her back to the Olympus. However, every now and then she would return to hell to be with her husband. In strong contrast to that, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, one can observe from the beginning an opposition between darkness and light. The first act of the creating God is to separate them and in all biblical narrations the light appears as the good and the night as the sinister. The gospel of Saint John and the letters of Saint Paul preach this antagonism repeatedly: on the one side there is light, on the other is darkness.

Both images, the one of celestial light and the one of infernal shadows, find their origin in one of the so many periodicities of nature: day and night. And both have their own space: The daytime space is the space of continuity, of perspective and clarity; in other words, it is a space where the sense of sight dominates and where, totally naturally, movement and action occur. The night space, by contrast, lacking horizon and luminosity, is a space of hearing and touching, that corresponds precisely to the senses that are especially strongly developed in blind people. But the nocturnal space is not defined only by a lack of light, in fact it has a rather unique and positive nature. Eugène Minkowski describes the

12 Hubertus Tellenbach, "Tres Concepciones Occidentales de la Noche," transl. Elvira Edwards and Otto Dörr, El Mercurio (9 September 1990), Cultural supplement Artes y Letras, E 19.

Figure 5: Multiplicity of spaces, loss of perspective."Farm" (pencil and crayon) 95 x 70 cm.11