because few matings can be more monstrous than the one of Queen Pasiphae and the bull with the divine force and whose product will precisely be a monster, namely the Minotaur. To approach God is terrible, monstrous, as Hölderlin says, but at the same time, without escape, without hope, for it is not possible to stay the same after knowing the divine, any more than it is possible to return alive from the labyrinth once one is being inside of it.

This interior atmosphere of the labyrinth that I have tried to outline appears in each of the versions of the myth and has been vividly reconstructed by a researcher of the subject, Paolo Santarcangeli, using thereby the following words:

The path was silent and the darkness was growing thicker. Of the hero's finger the thread unwound slowly, almost without an end. From time to time came noises and echoes, along the smooth walls, and like a blowing, a mooing of the wind. Of the wind? Then, there, where it must have been the innermost recess of

that dominated the fourteen Athenian youngsters who were brought inside the labyrinth every nine years and handed over to their dark fate was one of fright and horror. This horror was collectively perceived in Athens prior to the youngsters' departure toward Crete, during the period in which those who would be sacrificed were selected. It is precisely the sorrow of the entire people that pushes the hero Theseus, son of king Ageus, to join the group to get entry into the labyrinth to slay the Minotaur. It is necessary to keep in mind that the labyrinth is, by definition, a space that is very easy to enter, but very difficult or nearly impossible to leave. Moreover, it is a space that leads nowhere and the only thing that can be found there is a monster that is hidden in some kind of center. Nobody knows either where the monster is, that means the destruction of everyone who, whether out of free will or by force, enters that space. However, this monster also happens to be divine and as Franz Zinkernagel in his commentary on Friedrich Hölderlin's Oedipus writes:

The representation of the tragic is primarily based on the monstrous, such as God and man is mating, and the power of nature and man's innermost being becoming boundlessly one in wrath, thereby comes to comprehend itself that the boundless becoming one is purified by boundless separation.8

What does Hölderlin refer to with this boundless separation through which a cleansing from the boundless becoming one can be reached? I suggest that he alludes here to the subject of the labyrinth, for at least two reasons. First, because he refers to a space with boundlessness, something that is very characteristic of the labyrinth, which, in turn, is a way of cleansing, when a big mistake has been made. Second,

8 Friedrich Hölderlin, "Ödipus der Tyrann," in Sämtliche Werke, Erster Band, ed. Franz Zinkernagel, Leipzig, DE: lnsel Verlag 1927, pp. 824-875, here p. 874, transl. Existenz editors: "Die Darstellung des Tragischen beruht vorzüglich darauf, daß das Ungeheure, wie der Gott und Mensch sich paart, und grenzenlos die Naturmacht und des Menschen Innerstes im Zorn eins wird, dadurch sich begreift, daß das grenzenlose Eineswerden durch grenzenloses Scheiden sich reiniget."

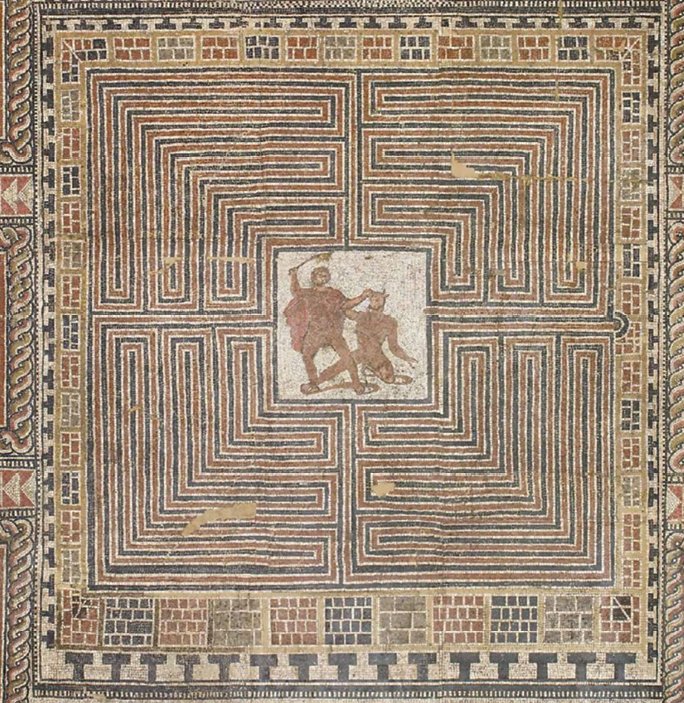

Figure 3: Partial section of a Roman polychromatic labyrinth representing themes regarding Theseus' journey to fight the Minotaur (marble and limestone mosaic), center 56.5 x 57.5 cm (LED 137).