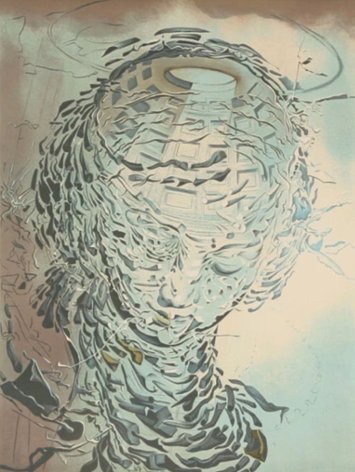

together.19 This painter's work calls to mind the aesthetic credo of twentieth century surrealism, associated with well-known names such as Salvador Dali and René Magritte and which nobody expressed so well as Comte de Lautréamont with his novel language that reveals a new form of beauty, for instance, this passage in the Sixth Canto that describes his perception of seeing a young passer-by:

and above all, as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella!20

et surtout, comme la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d'une machine à coudre et d'un parapluie!21

Mannerism arises from classicism as a need to overcome that harmony that is so characteristic of

19 © Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien https://www.khm.at/en/objectdb/detail/71/.

20 Comte de Lautréamont, "Sixth Canto," in Maldoror & The Complete Works of the Comte de Lautréamont, transl. Alexis Lykiard, Cambridge, MA: Exact Change 1998, pp. 188-219, here p. 193.

21 Comte de Lautréamont, Isidore Ducasse, "Chant Sixième," in Oeuvres Complètes: Les Chants de Maldoror, Poésies, Lettres, Paris, FR: José Corti 1987, pp. 321-59, here p. 327.

the latter and appears as a willful, forced search for originality in the disharmonic, in the ambiguous and, ultimately, in the absurd. In his 1944 essay regarding the formation of mannerism, Karl Scheffler writes:22

Mannerism...corresponds, speaking in a parable, to the state of the individual…when the generative potency experiences a crisis, as the individuals and the communities' sense that their creative spiritual powers have passed their peak. In this state, auxiliary forces of the will are called upon against the impending dangers, yet without daring to break with tradition.23

One always finds in mannerism a willful, forced, arbitrary element. This style is the opposite of getting carried away by contemplating nature in an attempt of imitating it, or by an emotion, be this profane or sacred. What other characteristics does mannerist art have? There are at least two. The first is related to the fact that in mannerist paintings, with exception of the portraits of individual persons, the figures are interlinked in a complex nexus of relationships with other figures, as is clearly observed in Michelangelo's "Final Judgement" and in almost all paintings by El Greco. In all these great artistic expressions, the figures, intertwined with one another, ascend in a

22 https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Cosmic--Exploding--Madonna/7A3A6F95DB937EF4.

23 Karl Scheffler, "Über die Entstehung des Manierismus," Werk: Die Schweizer Monatsschrift für Kunst, Architektur, künstlerisches Gewerbe 31/6 (June 1944), 169-171, here p. 170, transl. Existenz editors.

Figure 10: Salvador Dalí, labyrinthine elements in "Cosmic (Exploding) Madonna" (color lithograph on arches, 1958)73.66 x 40.64 cm.22

Figure 11: El Greco, "The Madonna of Charity"(oil on canvas, c 1603) 184 x 124 cm.24