from that suffocating and dingy prison (perhaps the concept of sin) by the action of a being of the light, of a god (as exemplified, for instance, in Theseus or Christ). And this is then the end of the myth of the Minotaur: Theseus, with the help of love (Ariadne), finally liberates humankind from its wickedness and animality, and from the contradictory nature of our hybrid condition, by destroying the monster and, by doing so, making the labyrinth unnecessary. In human history this will appear later only as an element of that so peculiar artistic style that is mannerism, but also as a central feature of schizophrenia, the modern way of manifesting madness.

Labyrinth, Mannerism, and Schizophrenia

The nexus between labyrinthine space and schizophrenia is formed by mannerism. It is, apparently, the first truly not naïf, not ingenuous style in art history. Mannerism arises around 1520 and lasts only for seventy years, as by 1590 it is replaced by baroque. There is no clear explanation of why it appears at that moment and the reasons

for its demise are not known either. Now, this was certainly not definitive, since isolated worshipers of it would appear in the following centuries, and it would return in all its glory and majesty through twentieth century surrealism.17

The first manifestation of mannerism is a picture painted in 1523 by Francesco Mazzola (also known as Il Parmigianino) representing himself, reflected in a convex mirror. This first mannerist picture shows almost all the characteristics of this artistic style that had been later defined in 1639 by Matteo Peregrini with reference to its seven sources:

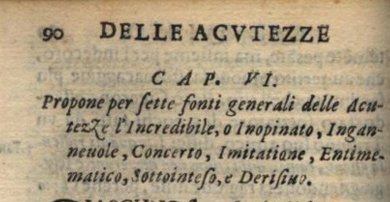

He proposes seven general sources of discernment: the incredible or unexpected, the deceptive, the involved, the imitative, the incomplete, the implied, and derision.18

Mannerism reaches its greatest achievements in Michelangelo's fresco The Final Judgment, painted between 1533 and 1541 behind the altar of the Roman Sistine Chapel (1541) and it adopts rather extravagant shapes in the Venetian style of Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto, and El Greco's work being its culmination. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, with this movement in the process of disappearing, another almost archetypical figure of mannerism arises: Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who composed human figures with fruits, plants, animals, and objects and succeeded in combining things of which nobody thought they could go

17 © Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, https://www.khm.at/objektdb/detail/1407/.

18 Matteo Peregrini, Delle Acutezze: Che altrimenti Spiriti, Vivezze, e Concetti, Volgarmente si appellano, Genova and Bologna, IT: Clemente Ferroni 1639, p. 90, transl. Existenz editors.

Figure 8: Matteo Peregrini's seven sources of Mannerism published in 1639.

Figure 7: Parmigianino, "Self-portrait in a convex mirror"(oil paint on convex panel, c. 1523) Ø 24.4 cm.17

Figure 9: Giuseppe Arcimboldo,"Summer" (oil paint on canvas, 1563) 67 x 50.8 cm.19