The failure of the attempt on Adolf Hitler's life on July 20, 1944, carried out by the Colonel and Chief of Defense Staff, Count Claus von Stauffenberg, had terrible consequences for the conspirators, Germany, and Europe in general. Around five thousand people directly or indirectly linked to the Resistance movement were executed between that date and the end of the war. The attempt was not well understood by the allied countries nor by the German people themselves. In 1946 Winston Churchill paradoxically expressed the first-ever official recognition of the Resistance.

The Resistance against the National Socialist dictatorship started much earlier and was much more important than people tend to believe. Many of the high-ranking officers of the Wehrmacht participated in it, among whom Kurt von Hammerstein, the last general in chief of the army before Hitler assumed power, as well as Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, and General Ludwig Beck. They carried out innumerable attempts, first of coups d'état and later of murdering the tyrant, all of which devilishly failed.

In contrast to the National Socialist authorities, most of the conspirators were refined people of great culture. In this essay, I analyze the relationships that Stauffenberg, the executor of the last attempt, had with poetry and with music, by contributing with some unpublished data in this regard. Likewise, I will reproduce the two poems the poet Stefan George on his death bed supposedly gave the hero eleven years before the attempt, and which undoubtedly kindled a mission that Stauffenberg became aware of only later. Another important element of this story is the fact that many of these Wehrmacht officers in the Resistance greatly admired the poet Rainer Maria Rilke to such extent that they employed the last lines of his Requiem as a motto for strengthening their own resolve:

Who speaks of victories: To withstand is all.

Eighty years have passed since the attack against Hitler was carried out by Stauffenberg, as part of a plan long prepared by the high German officiality that aimed to end the war, liberate the occupied countries, set the prisoners in the concentration camps free, and reinstall the rule of law in Germany. His daughter Konstanze von Schulthess points to the fact that the attack was not well received nor understood by either the Allies or the German people. For instance, on August 2, 1944, Winston Churchill addressed the House of Commons with the words:

In Germany, tremendous events have occurred which must shake to their foundations the confidence of the people and the loyalty of the troops. The highest personalities in the German Reich are murdering one another, or trying to, while the avenging Armies of the Allies close upon the doomed and ever-narrowing circle of their power.

The New York Times of August 9, 1944, reports that

the details of the plot suggest more the atmosphere of a gangster's lurid underworld than the normal atmosphere one would expect within an officers' corps and a civilized Government. For here were some of the highest officers of the German army...plotting for a year to kidnap or kill the head of the German state and Commander in Chief of its army; postponing the execution of the plot repeatedly in order to kill his high executioner as well; and finally carrying it out by means of a bomb, the typical weapon of the underworld.

Marion von Dönhoff who had joined the resistance movement and after the war entered a successful career as a journalist, objects to this portrayal of events:

Nobody can imagine today what it may mean to love one's fatherland and simultaneously wish for its defeat.

The attitude shown by the allies toward the Resistance movement can be deduced from the words spoken by the British Foreign Affairs Minister Anthony Eden who, according to Dönhoff, said that he would not answer "to these people" as he considered them to be traitors. Later, Eden allegedly noted:

It is our opinion that they are of no use to us nor to Germany as long as they do not reveal their hand and give a visible sign of their intention to assist in the disempowerment of the Nazi regime. [EW 27]

Despite numerous attempts by the resistance movement to establish contact with the Allied Forces, including the United States, there was no openness to distinguish between Germans and Nazis. Dönhoff, in trying to understand the incomprehension the Resistance received from the international press, writes:

Despite knowing better, the Americans too maintained the lie that there was no German resistance and no Germany other than that of the Third Reich. [EW 28]

Regarding the Germans, it should be recognized that for many of them, this act also meant a betrayal of the legitimate authority. This idea persisted for an entire decade. Only in 1954 was there a gesture in favor of the resistance movement participants, when the president of Germany, Theodor Heuss, in a 1954 speech before the students at the Free University of Berlin, expressed his respect for the Resistance when he laid out the contrast between one's right for resistance and compared it to one's duty for resistance. His affirmation of the historic lawfulness of the Resistance and his gratitude to its participants are clearly present in his speech:

Yet the giving of thanks is done with the knowledge that the unsuccessfulness of their efforts does not deprive the symbolic character of their self-sacrifice of its honor...the excruciating torture brought the same torment to them all, and death by hanging, intended to disgrace them, or death by the bullet, in order to merely annihilate them, the self-chosen death out of despair brought to all of them the same entitlement that the gratitude values their sacrifice highly as a gift for Germany's future.

In a mixture of revenge and deterrence, Hitler ordered consanguinity liability (Sittenhaft) and threatened to punish all descendants of anyone who even remotely was involved in the assassination attempt. Later, he extended this punishment method to his own officers if they were unsuccessful in battle (RW 259). The relatives of the executed conspirators, besides being expropriated of all their assets, did not receive any support from the Federal Republic until the mid-1950s. The heroes obtained a certain recognition only in 1964, when some streets received their names and monuments were erected, although in my opinion, not enough of them. Books about the subject were published too. Since then, every year official ceremonies have been organized in their memory.

Paradoxically, they received the greatest and earlier recognition already in 1946 from Winston Churchill himself. The historian and physician Eberhard Zeller recounts the following:

Winston Churchill, who immediately after the July attempt had said some unkind things, is reported to have made this remark in the House of Commons in 1946:

"In Germany, there was an Opposition which was quantitatively weakened by its sacrifices and by an unnerving international policy (Casablanca!) but which was among the greatest and most noble groups in the political history of all times. These men fought without help from inside or outside—driven solely by their uneasy conscience...Their deeds and sacrifice are the foundation of a new edifice. We hope the day will come when this heroic chapter of the internal history of Germany is duly appreciated."

However, Zeller is cognizant of the fact that the British viewed favorably the failure of the attempt. He refers to the English historian John Wheeler-Bennett who

defends Britain's policy of ignoring the revolutionary movement in Germany...And he offers this revealing explanation: otherwise the Allies would have had to agree to a negotiated peace, and that "would have been to abandon our declared aim of destroying German militarism." Equally, he is convinced that a successful coup would have led to a negotiated peace. [FF 386]

The Resistance against the Nazi regime was much more important and precocious than one would think, and it began, strictly speaking, already before Hitler assumed power. The disqualification that the Nazi authorities made of them, by treating them as "a small group of ambitious and criminal aristocrats," does not correspond at all to reality. In fact, to that movement belonged not merely aristocrats, both military and civilian, most of them catholic, but also many who did not belong to the nobility, such as conservative, social democrat and communist politicians, intellectuals, and artists, catholic priests and Lutheran clergymen, and so on. Very soon, German aristocracy, with some exceptions, took its distance from Hitler and his movement and ideas. They somewhat despised the Nazi movement due to its socialistic ideas, but above all, because of the personality of the leader, Hitler, a simple army corporal with fanatic features. Besides, opposition against Hitler was very strong among catholic officers since the Catholic Church was more decided than the Lutheran in its commitment to the anti-Nazi fight. The relative weakness of the Evangelic Church is shown by the fact that an important group of Lutheran intellectuals felt morally obliged to create another church, the so-called Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church), which the most important Lutheran members of the Resistance joined; among them Peter Yorck von Wartenburg and Helmuth von Moltke.

But there is nothing more suitable to evaluate the role of aristocracy during this terrible period of German history than a speech delivered on the occasion of the July 20 anniversary by Count Alexander von Stauffenberg, the only survivor among the brothers, and later Professor for Old History at the University of Munich:

As regards the preponderant share in this revolt of German aristocrats from every noble family: any German who does not suffer from class bias, will be proud to know that the most ancient and aristocratic families of the Reich, who are known to have lost their "privileges" generations ago, once again claimed their original right: the right to give a lead to the German people by their way of life and to do so in death. [FF 448n13].

Among the members of the Armed Forces, it is worth outlining at least the most famous participants, such as Field Marshal Rommel, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, former General in Chief Baron Kurt von Hammerstein, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, Generals Ludwig Beck, Friedrich Olbricht, and Karl Heinrich von Stülpnagel, and Colonels Stauffenberg, Henning von Treskow, and Werner von Haeften. Among the civilians, one should mention the Minister of Economy, Johannes Popitz, Secretary of State Erwin Planck (son of the great physician Max Planck, creator of the Quantic Theory and Nobel Prize recipient in 1918), former Leipzig Mayor Friedrich Goerdeler, important jurists such as Hans von Dohnanyi, Counts Moltke and Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, priests such as Agustin Roesch, Alfred Delp, Rupert Mayer, and Lothar König, and the Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (the son of the renown psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer, Professor at Berlin University). The socialist politicians who participated in the Resistance include Julius Leber, Wilhelm Leuschner, Theodor Haubach, and Eugen Gerstenmeier. Almost all of them were executed after the attack. Of those named above, only the Jesuit König who miraculously managed to escape, and Eugen Gerstenmeier to whom the People's Court in the last moment commuted the death penalty to prison (FF 100), survived. Many other members of the Catholic Hierarchy collaborated decidedly with the Resistance, although without participating in the preparation of the attacks in a direct form. The most notable cases are those of the Archbishop of Berlin, Konrad von Preysing, and the Bishop of Münster, Clemens von Galen (EW 57). It is well known that the Resistance received great help from the Vatican, not only economic support, but also concrete actions oriented to establishing contacts with England. These aimed to warn about the danger Hitler meant for the world peace and to avoid the imminent war.

It is interesting that most of the members of the Resistance were people of a high intellectual level and great culture. Stauffenberg, for example, besides being a senior officer, was a poet and a musician. In fact, at some point in his life, he wavered between following a career as a cellist or joining the military (ZF 32). He was also inclined to study architecture. Finally, he decided to join the army, partly moved by family tradition and by his love for Germany. Nevertheless, he never abandoned his intellectual interests and so, some of his survivor companions remember him avoiding in the regiments the glamorous casino life and fundamentally dedicating himself to reading and to music. Officials under his command remember Stauffenberg's appreciation of August Neidhardt von Gneisenau's classical phrase:

An officer ought to demonstrate "education in times of peace, yet courage in war." [ZF 49]

The influence of his mentor, the poet Stefan George, remained throughout the years. He would read his poems almost daily and knew many of them by heart. Let us remember that Stauffenberg himself was a poet, and George found his poems excellent and continuously stimulated him to follow through with his poetical nature (ZF 31). But George's influence goes further than literature. He conveyed to the brothers a sort of idealistic image of Germany, which they were to rediscover and promote. His political ideal for Germany, Das neue Reich, was originally a book of poems, but later it became a kind of project for a new Germany. George considered himself an educator of a new youth, where he saw the new spirit from which the new kingdom should emerge. He saw the future new spirit rooted in a secret Germany. The influence of Stefan George left a heavy mark on the brothers, especially on Berthold and Alexander. Claus, however, was more independent and he understood the new kingdom rather in terms of doing a service for establishing a better order.

His brother Berthold was exceptionally talented: he was a jurist and researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Berlin, spoke seven languages, was a philologist, and, at the time when he was executed, was working on a new translation of the Odyssey from Greek into German. The description a surviving friend of his made about some of the details of the translation is fascinating. Berthold always searched for a sentence in German that better reproduced the musicality of the original verses of Homer (FF 424-5n33).

Another example of a gifted member of the Resistance was Peter Yorck von Wartenburg. He was a jurist as well, but also a literature expert and a polyglot. His grandfather was the great German philosopher of the nineteenth century, Count Paul Yorck von Wartenburg, who was a close friend of Wilhelm Dilthey (EW 114). As an example of his magnanimity, it suffices to remember that the renowned Chilean jurist and philosopher Carlos Peña extensively quotes him in his recent and notable book El tiempo de la memoria. The library of his family's castle, where Peter, the hero, grew up, counted 150,000 volumes and his love of literature was such that he knew more than one hundred poems by Goethe by heart (EW 115). He was a very close friend to Count Moltke, also a jurist, and together they oversaw the redaction of the new Constitution for a future Germany without Hitler.

General Baron Kurt von Hammerstein was a man of great intelligence and culture and was so admired by the German army, that Hitler, even knowing that he was his enemy from the very first day, did not dare to have him murdered which was what he did with so many others, such as, for example his defense minister Kurt von Schleicher, who besides Hammerstein was one of the other conspirators to block Hitler's nomination to become Chancellor. Adam von Trott zu Solz, jurist and diplomat, did his postgraduate studies in Oxford at the beginning of the 1930's and was much admired among his peers for his intelligence and his culture, and used to be invited to houses of emblematic figures of English politics and aristocracy, such as Lord Halifax, Lord Astor, and Lord Lothian, among others, where he met Winston Churchill (EW 155-60). All this stands in strong contrast to the type of people in Nazi leadership, who had no university formation, were primitive and uneducated, and showed evident psychopathic and antisocial behaviors. The new research conducted by Norman Ohler in numerous archives in Germany and the United States regarding the diary of Theodor Morell, Hitler's personal physician, shows to what extent the Nazi leaders, including Hitler himself, were heavily dependent on drugs, particularly morphine and amphetamines. However, also the young soldiers who at the beginning of the war fought the Blitzkrieg, and the young marines in charge, at the end of the war, of suicide missions in small submarines, were stimulated by high doses of methamphetamine.

Many have reproached the Resistance to have acted late when the war was already lost, but this does not correspond to reality. The attack of Count Stauffenberg was the last of a long series of attempts, first of coups d'états with the object of removing Hitler and judging him and then, due to the repeated failures, of direct attacks against the dictator's life. The most important attempt of a coup d'état took place in September 1938 and was aimed at preventing the war Hitler wanted at all costs. Dönhoff reports that this attempt was organized by Generals Ludwig Beck, Hans Halder, and Erwin von Witzleben, in collaboration with Kurt von Hammerstein (EW 177-8). The operation to assume power and to neutralize the elite corps (SS) was prepared to the last detail. The plan was made known to the English authorities who were begged not to accept Hitler's expansionist intentions. They ignored the warning and sent Neville Chamberlain, who ended up accepting Hitler to occupy part of Czechoslovakia. This great diplomatic triumph of the dictator would have made a coup d'état very unpopular at that moment and the operation had to be cancelled. Friedrich Goerdeler, the mayor of Leipzig then sent a letter to the United States government, that included the following paragraphs:

The Munich agreement was nothing but a complete capitulation by France and Britain to inflated charlatans...The end of the German people's sufferings under a brutal tyranny...has been deferred for a long time...we knew from our suffering what course the satanic and demonic Hitler would take. In spite our warning¸ Chamberlain ran after Hitler in 1938. [FF 34]

The ethical problem that the murder implied was resolved when the high officiality verified the massacres carried out by the SS in the rear guard of the Russian front and the mass murders in concentration camps (FF 157). Nevertheless, many of the members of the Resistance did not agree with the assassination of Hitler, like the already mentioned counts Moltke and Yorck. Being a survivor of the Resistance, Dönhoff writes in this respect:

Peter Yorck realized very early on that a coup was inevitable and that he had to fully commit himself to it. But for him, as well as for Moltke, who both consciously lived as Christians, the idea of systematically organizing Hitler's assassination was a difficult problem that troubled others far less. Moltke refused to eliminate criminals by committing a crime. Yorck did not share his opinion quite so unequivocally, and in the final phase he then fully brought himself to do the deed. [EW 132]

Of the generals implicated in the rebellion, not all agreed with the murder either, for instance, Field Marshal Rommel. However, for Stauffenberg and several others, the moral question was completely clear. Gerstenmeier describes this sentiment:

We had tried to do what we thought we owed Germany and the world before God and our conscience; we had done it with the means which we were able to get hold of, after careful planning and endless efforts. The rest was in God's hands. [FF 101]

Stauffenberg did not need to convince the young officers, for his mere presence was enough. They trusted him and found in him the power to go through all difficulties and begin something new. The high officiality was also scandalized by the brutalities committed by the SS commandos on the civilian population which showed some sort of oppositional attitude or conduct to the regime. Dönhoff reports that Moltke, who worked in the judicial branch, tells his English friend Lionel Curtis in a letter from April 1942 the following:

The number of Germans who are currently still being legally executed by sentence of a regular court is 25 per day and at least 75 per day by court-martial. Hundreds are killed daily in concentration camps and by firing squad without trial. The constant danger in which we live is abominable. [EW 111]

Zeller's review of the acts of the Ministry of Justice shows that the number of executions in 1943 was 5,764 (FF 430n11). All this led to the situation that from the beginning of 1942 and up to July 20, 1944 no more attempts of coups d'état would happen—something that would have been impossible by that time—but exclusively attacks against Hitler, according to Dönhoff's account consecutively carried out by Henning von Tresckow, Fabian von Schlabrendorff, Rudolf von Gersdorff, and Axel von dem Bussche (EW 40-6), before those of Stauffenberg—which were not one, but three, on July 11, 15, and 20—all of which diabolically unsuccessful. I will not extend on the details of the last one as it is well known through films and documentaries, but I would like to remember its terrible consequences: more than half of all deaths in the Second War occurred between July 20, 1944, and the capitulation on May 8, 1945; Hitler had some three-hundred conspirators or suspects executed in the first days after the attack, among them, according to Dönhoff, were nineteen generals, twenty-six colonels and commanders, two ambassadors, seven diplomats, three secretaries of state, the chief of police, several priests and theologians, and numerous senior officials of the most diverse ministries and governorates (EW 36). Zeller points out that in the later period and until shortly before the end of the war, around five thousand more people were executed due to the attack of July 20 (FF 380).

What is not well known is the relation of the Resistance with the poetic world. Stauffenberg's extraordinarily cultivated mother was a friend of Rainer Maria Rilke and she spoke with him about her talented young sons. Rilke, after meeting them, wrote to their mother that their facial expression showed they would have a great future. Nevertheless, no further close contact resulted from this encounter. Yet different was the situation with the other great German poet of the first half of the twentieth century, Stefan George, who was introduced to Countess Stauffenberg by Paula Kröner, the wife of a famous publisher from Stuttgart (ZF 24). The poet was immediately interested in the three young Stauffenberg boys, especially in Berthold and Claus, and incorporated them into the closest circle of his followers. George showed a rigorous intellectual incorruptibility against the spirit of the time and the prevailing trends, and he wanted

to counter the confusions of the present age with a secret Germany that harbored the dormant forces and ideals of the nation and whose means of communication was to be the aesthetically flawless form. [ZF 26]

This secret Germany would hide the forces and the ideals of the nation, whose means of understanding should have an aesthetic, immaculate form. George wanted to take distance from every manifestation of mass culture. His high aesthetic aspiration was shown by his extremely elaborate, elevated, and baroque language. His disciples had to exercise this language and write poems that were presented to the master. He also demanded that his followers truly identify with his poetry and never take a determined political option. He considered political debates nonsense. The Stauffenberg brothers belonged to this circle in heart and soul.

George did not demand that the brothers isolate themselves under something like a consciousness of belonging to an elite; he rather wanted them not to lose themselves in everyday life and to never forget the promised ideals. George was very influential for Claus. He taught him to never submit himself to the prevailing trends. The memory of George helped Claus to always keep a distance and, thanks to many of George's poems that he knew by heart, he managed to have his own original style in his relationships with his friends and comrades. The Stefan George Circle somehow continued to exist after the poet's death in December 1933. My professor during the 1960s in Heidelberg, the great psychiatrist and philosopher Hubertus Tellenbach, also belonged to this circle and he told me on one occasion, in 1966, that he had heard that Stefan George had given Claus the mission of "murdering the tyrant," putting in his hands two poems related to the subject: "The Antichrist" (Der Widerchrist) and "The action" (Die Tat). This was confusing for me as the attack took place in July 1944, that is, eleven years after the poet's death. Tellenbach also told me that the motto used by the members of the Resistance for recognizing themselves was the above-quoted verse by Rilke: "Who speaks of victories. To withstand is all." However, as time went by and already mature, I rekindled my love for Rilke, and I translated his Elegies and his Sonnets into Spanish and published them in a bilingual edition; I was also very interested in the details of his life, and, by chance, in a biography of him I found a quote of the poet Gottfried Benn, referring to the role that verse had in his generation of opponents to the Nazi dictatorship. Something similar happened in the context of the anecdote of George. After the said conversation with Tellenbach I became interested in the Resistance movement and one day I found in a biography of Stauffenberg a whole chapter dedicated to the relationship of the three brothers with the poet (ZF 24-32), describing the same history of the great influence George had on Stauffenberg, but in more detail: the poet went to Minusio in Southern Switzerland into exile shortly after Hitler's accession to power and he told his disciples: "we are being governed by mentally inept people" (ZF 51). There George became ill and, already at death's door, the three brothers went to Locarno to accompany him. The poet appointed Berthold, the oldest of the three brothers, as his heir. Steinbach does not mention in his book that George gave Claus these two poems that Tellenbach had mentioned to me. Nevertheless, there are two instances where Steinbach describes facts in complete consistency with Tellenbach's comment. First, when he ends the chapter dedicated to the relationship between the Stauffenberg brothers and the poet with the sentence:

He [George] instilled in the young Stauffenberg a perception of the potentiality that public circumstances could also end up being at the mercy of a person whom he considered to be the "Antichrist." [ZF 32]

And second, when Steinbach addresses in the subsequent chapter the relevance of George's poetry for Stauffenberg's followers:

For them, his poetry meant a legacy. Special significance kept for Stauffenberg "Der Widerchrist"...This poem was published in 1907, the year Stauffenberg was born, and witnesses George's will not to abandon himself to "cherishing contemplation," but to strive for "transformative deeds." There are also other poems with a similar purpose, such as "Der Täter" (The Doer) or "Der Empörer" (The Rebel). [ZF 41-2]

Furthermore, also the historian Zeller, in his extraordinary book regarding July 20th, 1944, which he had written shortly after the events took place, mentions the importance of the poem "The Antichrist" for the conspirators. Zeller also reports that Countess Maria Stauffenberg, Berthold's widow, told him that someday before the attack, her brother-in-law Claus showed her the poem "The Antichrist" that he was reading in George's book, Der siebente Ring. Zeller writes:

The Countess suggests that Claus Stauffenberg sometimes quoted it to win over men still hesitating to join the Resistance. And she says the poem circulated among Stauffenberg's associates as a sign of identity of those ready to take action. [FF 425n4a]

In the revised literature I have not found confirmation that George in his last minutes of life also gave Claus the poem "The Action," as Tellenbach stated, but it seems highly probable to me, considering George's constant position against the prevailing opinions, manifested among others in his poems "Die Tat" and "Der Täter" (The Doer), along with the development of the events.

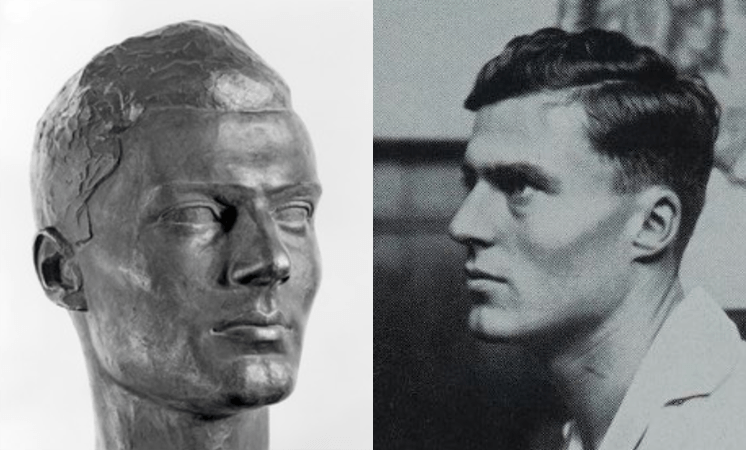

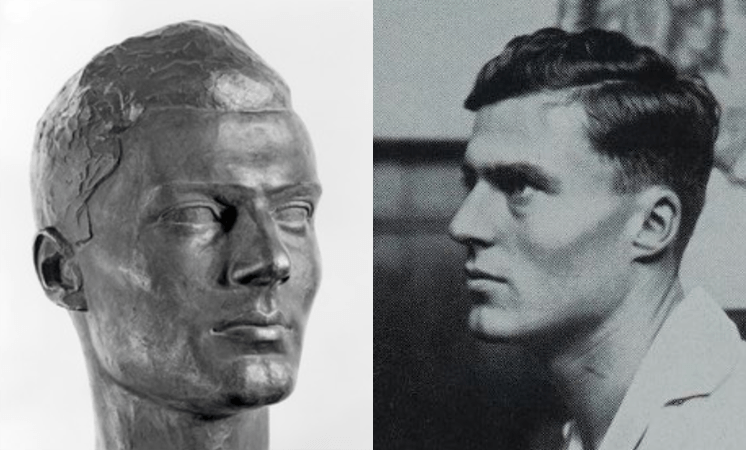

Left: Frank Mehnert's Claus von Stauffenberg bust.

Right: Claus von Stauffenberg in the atelier of Frank Mehnert in 1929.

In his book on George, Robert Boehringer tells an anecdote of an incident in which George showed him a newly crafted bust and asked Boehringer for his opinion about it. The young sculptor Frank Mehnert stood directly next to the bust, yet Boehringer did not know who had created it. Boehringer looked at the bust for a long time, walked around it a few times, and said: "Murderer." George reacted visibly upset. Only at a later time did Boehringer find out that it was the bust of Stauffenberg that he had been asked to judge. Regarding this event, Wolfgang Venhor reflects upon its significance by stating that in the symbol-laden language of George's circle, "murderer" could stand for "doer," "man of action." Be it as it may, just one year before this event, George had received this poem written by Claus:

And the clearer the living stands before me

the higher the human reveals itself and

the more urgently the deed shows itself

the darker one's own blood becomes

the more distant the sound of one's own words becomes

and the rarer the meaning of life

presumably until one hour in the hardness of the blow

and in the magnitude of its appearance

gives the cue.

In conclusion, I present here parts of my English version of some relevant verses by George. Toward the end of the first poem, "The Antichrist," the poet exclaims:

The prince of vermin spreads his realm,

He lacks no treasure - no bliss is evading him...

Have the rest of the rebels go under!

The second poem, "The Action," ends thus

He pays no heed to the well-meaning words of other creatures,

He rushes on with the wild steps of a boy,

And defended by the naked sword in his hand,

He has slain the monster, bathed in poison and blaze.

He follows his path, lit by the burning torch,

His beautiful eyes fixed silently and straightforwardly on the horizon.

The verses speak for themselves. One cannot know to what extent Stauffenberg understood the mission entrusted to him, but Zeller recounts that Berthold's widow told him too that, in the last days before the attempt to murder Hitler and in the middle of bomb attacks, Claus, sitting on the balcony, recited these verses to himself (FF 425n4a). Many years later, when I was revising Stefan George's work, of which Claus knew one hundred poems by heart, I found a poem dedicated to the hero that I had not known and that portrays him in an unparalleled manner:

You are dear to us – yet you also puzzle us –

Your smile is playing: recognize the chasms between us

As unfathomable, like me

And uphold their secret – yes, exult

Never be able to grasp them... and we painfully seek

To bridge them with our love

and follow, without fear, your transformation:

From your countenance radiates the gaze of the victors.