fashionable, which, in the case of the Bomarzo Palace of the Orsini family, are filled with monsters and are thereby providing a quintessential example of mannerism. Baroque poetry and prose are also labyrinthine and the finest examples of that time are the works of Luis de Góngora and Baltasar Gracián. In his famous novel El Criticón, Gracián describes the world of his hero as a "model of labyrinths and a center of minotaurs,"26 he then adds:

It was spacious and not at all proportionate, nor was it square: all angles and traverses, without perspective or concinnity. All its doors were false and no opening discernable. [EC 235]

In the eighteenth century the most outstanding figure

26 Baltasar Gracián, El Criticón, ed. Miguel Romera-Navarro, Lancaster, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press 1938, p. 228, transl. Existenz editors. [Henceforth cited as EC]

in terms of employing the subject of the labyrinth is without a doubt the Italian engraver, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778),27 who drew his famous motif of Prisons with infinite ladders and mirrored corridors that have inspired part of the work of an interesting contemporary Chilean painter, namely, Eduardo Meissner Grebe.28 In the nineteenth century, with the predominance of romanticism and of neoclassicism, the labyrinth disappeared as a subject, to return in all its glory and majesty with surrealism. I could not end this brief historical review without mentioning the great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, who in spite his concise style, also frequently got involved with mannerist subjects such as the labyrinth and mirrors. In one of his stories, El Aleph, he writes:

I dreamed, until I was exhausted, of a clean, small labyrinth in whose center was an amphora, that my hands almost touched, that my eyes contemplated, but the paths were so confusing that it became clear to me: I would die without ever getting there.29

Moreover, his story "The garden of the Y-junctions" is labyrinthine in all possible senses, from the argument and the description of landscapes and gardens to its unexpected and surprising end.30

In summary, the curious movement that appeared in the sixteenth century and that had important though isolated worshippers in the following centuries, is full of divisions, whims, and contradictions, its most recurrent subjects being the labyrinth, the mirror, the mask, the artifice, the monstrous, and the uncommon association. I suggest all these characteristics suspiciously bring mannerism closer to the schizophrenic world. Everybody knows that from the first descriptions of this disease made by Emil Kraepelin and Eugen Bleuler one can find references to stereotyped and mannered movements, gestures, conducts, expressions, and thoughts

27 https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/2969.

28 © Rosemarie Meissner-Prim, private collection.

29 Jorge Luis Borges, "El Inmoral," in El Aleph (1949), Obras Completas I (1923-1949), Buenos Aires, AR: Sudamericana 2016, pp. 833-45, here p. 835, my translation.

30 BG 113, Case 91, fig. 68. © Sammlung Prinzhorn, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg.

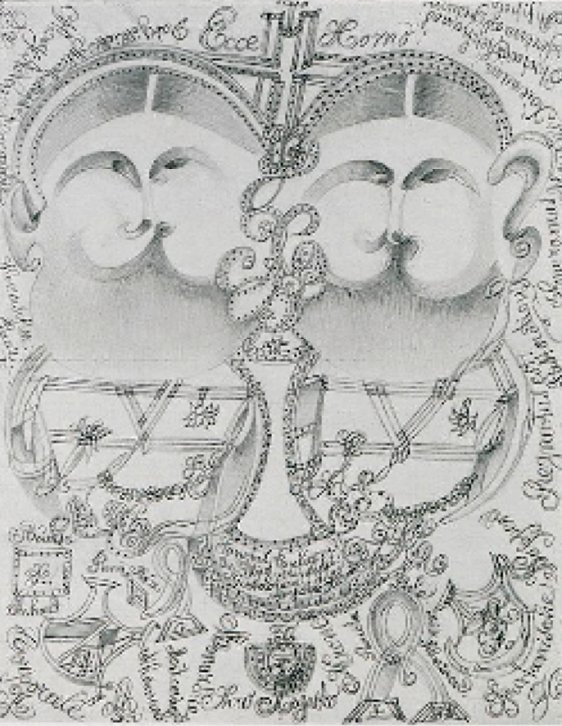

Figure 14: Mirroring motif, monstrosity, labyrinth: "Ecce Homo" (pencil) 33 x 42 cm (slide 36).30