always refer to the "lived space" as it is understood by Erwin Straus, and not to the objective, geographic, or geometric space. Straus writes:

If we want to represent the primary experience of space, we must free ourselves from the concept of space in physics and mathematics. We must be careful not to allow any prejudices or anticipatory decisions to be imposed on us, even if they stem from the proven experience of other sciences. For these are logically and systematically the later ones, even though they were developed historically earlier than the analyses of the primary forms of experience.3

Yet this does not mean that the one concept has nothing to do with the other one. The lived space presupposes the existence of a physical or objective space, and it is defined by three characteristics:

Mood

The first characteristic of lived space is that it is always marked by how a person feels on the level of emotions; it is a space colored by the basic humor or mood of the person who lives in it; nonetheless, the mood of the one who lives in any given space is in turn influenced by the objective space of the surrounding. In German language the word Stimmung is used for both, the mood of a person and the ambiance or atmosphere of a landscape. Therefore, one could argue that the space pervaded by humor represents a particular way of self-world relation, in which both elements of the duality are inextricably united, prior to any separation between the subjective and the objective. Thus, if, for any reason related to one's biography, we wake up happy and we are in a very good mood, the space surrounding us (our house, the garden, the landscape) will seem joyful and beautiful to us too. In contrast, a cloudy sky, and low and dark rain clouds under which

3 Erwin Straus, "Die Formen des Räumlichen: Ihre Bedeutung für die Motorik und die Wahrnehmung (1930)," in Psychologie der menschlichen Welt: Gesammelte Schriften, Berlin, DE: Springer Verlag 1960, pp. 141-78, here p. 142, transl. Existenz editors. [Henceforth cited as FR]

associated with the essence of a human being as it has been convincingly argued by Timothy Crow.1 I will start by making a phenomenology of the labyrinthine space in comparison with the human space.2

Phenomenology of the Labyrinthine Space

Above all, let me be clear that in this study I will

1 Timothy J. Crow, "March 27, 1827 And What Happened Later—The Impact of Psychiatry on Evolutionary Theory," Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 30/5 (July 2006), 785-796.

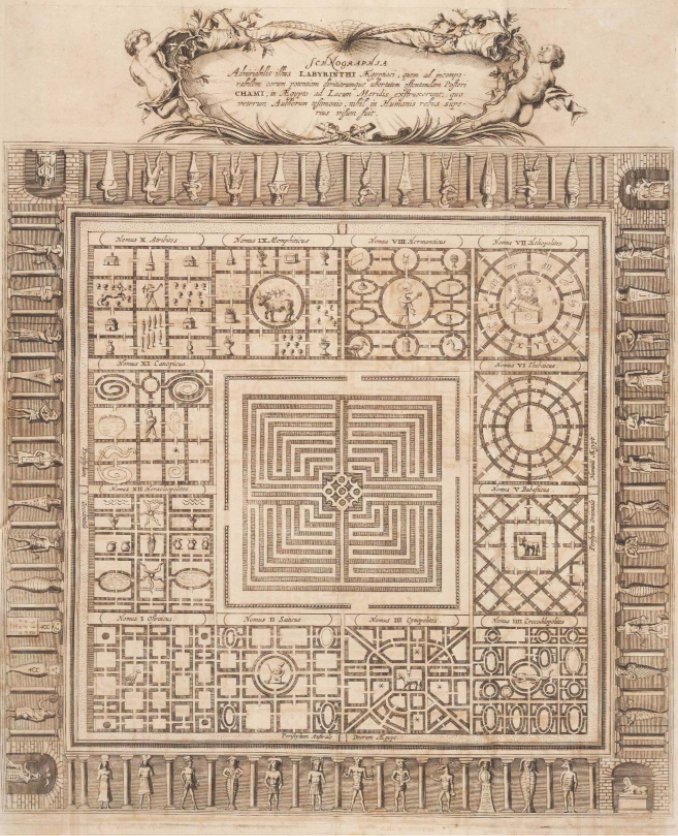

2 Athanasius Kircher, Turris Babel, Amstelodami [Amsterdam, NL]: Ex officina Janssonio-Waesbergiana 1679, copper-engraved fold-out plate between pp. 78-9.