without cataloguing the subtle differences between imperatives and normative propositions. Frankly, many lawyers most likely practice law without ever wading too deeply into philosophical analyses of law. The difficulty for building law abiding machine weapons is that many of the distinctions highlighted in the philosophy of law are somewhat intuitive to most people but may be quite difficult to formalize in a machine architecture. As a child, I had little difficulty recognizing that the threat of punishment implicit in deciding to ignore my parents' orders—formalized, for example, by the command CHORE—made them very different from the normative propositions governing a game that I had freely chosen to play with friends. The challenge is not in understanding these differences, so much as it is in representing them in a computer model that is adequate to realize legally compliant behaviors in the world. In a 1998 interview Daniel Dennett remarks:

There's no place for impressionism in creating a computer model or an algorithm…Computers force you to get clear about things that it's important to get clear about.14

Perhaps surprisingly, making clear the conceptual distinctions of moral and legal philosophy may be far more important to building ethical LAWS than they are to human soldiers, who can intuitively grasp normative differences although they might struggle to formulate them.

The Heterogeneity Problem

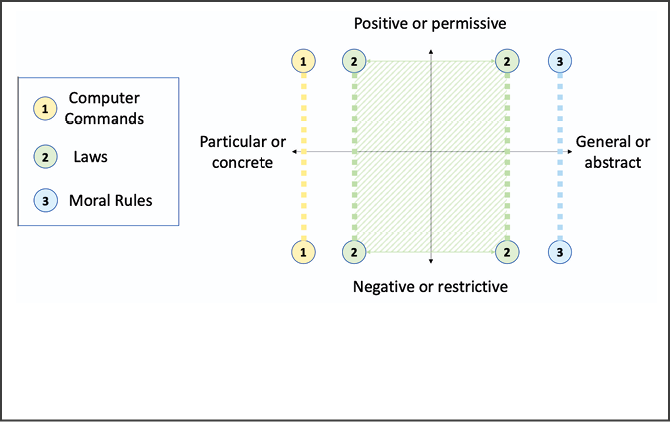

Whether the law consists exhaustively in rule-following, or whether it consists in following rules and other rule-like contents, the variety of legal contents makes law-following more difficult. In the previous section I suggested that one potentially important difference is that laws vary in terms of the source of their normative authority. In this section, I want to emphasize two other important ways that laws differ—as rules of one type or another—that are especially relevant for present concerns. First, laws vary significantly in the generality or specificity

14 Harvey Blume, "A Conversation with Daniel Dennett," The Atlantic Online, 9 December 1998, https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/digicult/dennett.htm.

of both the circumstances in which they apply, and in the nature of their action-guiding content. Some rules prescribe a very specific act in response to a very specific condition or circumstance. Alasdair MacIntyre describes these rules as maximally concrete such that "there is no such thing as understanding the rule and not knowing how it is to be applied."15 Other rules are abstract in that they might fully determine some set of more concrete rules.16 For example, a relatively abstract rule like, "You should always treat people with respect," fully determines any number of rules about how a person ought to treat others in a particular case. Second, rules vary in the extent to which they are either prescriptive or proscriptive; for instance, rules such as CASTLE make allowances for acting in certain ways, while rules such as OPEN levy requirements. Still other rules prohibit or discourage behaviors, although I have not offered an example of either case. It should be enough to say that differences in the ways that a rule guides action, coupled with differences in type and generality, present several distinct challenges for rule-following.

The best approach to demonstrating these challenges may be through direct comparison of

15 Alasdair Maclntyre, "Does Applied Ethics Rest on a Mistake?," The Monist 67/4 (October 1984), 498–513, p. 503.

16 David A. Vogelsang and Mark D'Esposito, Is There Evidence for a Rostral-Caudal Gradient in Fronto-Striatal Loops and What Role Does Dopamine Play?," Frontiers in Neuroscience 12/242 (April 2018), 1-11. p. 2.

Figure 1: Rules vary according to the permissiveness or restrictiveness of their action guidance (y-axis) and according to the generality of the guidance of the rule (x-axis). Laws tend to occupy an intermediate space in terms of their generality, but admit of both permissive and restrictive cases.